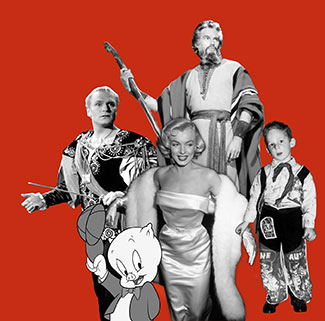

This is the continuation of an analysis of Marc Shell’s 2005 book, Stutter. (See part 1 here.) As described in the previous installment of this three-part review, Shell examines the phenomenon of stuttering as it pertains to four figures from popular culture: Moses, Hamlet, Marilyn Monroe, and Porky Pig. This part looks at his assessments of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and the famous movie star Marilyn Monroe.

In Apprehension, How Like A God

After reading Hamlet in high school, Shell sought to prove a point about the play to his classmates. He claimed the character of Hamlet stuttered, although this was not explicit in the text. To prove his point, Shell “look[ed] through the play for ambiguous references to something like physical disabilities.” He finds instances of Hamlet displaying secondary characteristics of stuttering including deliberate repetitions, singsong rhyming, word substitution, unexpected pausing during speech, avoidance behaviour, and expressions of paralysis, both physical and mental.

Shakespeare used real people and events from history as source material for almost all his plays, and there are hints that the Roman emperor Claudius, a stutterer, was one of the historical models for Prince Hamlet. Claudius used his stuttering to his advantage in order to appear docile in a treacherous world of potentially fatal political and familial rivalries. Hamlet, whose own father has been murdered and his mother wed to the killer, also has good reason to fear. His lapse into “stuttering” or impeded speech can be seen an act of self-preservation. Should he flee? Seek revenge? Turn to the authorities for justice? He does none of these things. He must, in his words, “make his tongue and soul be hypocrite” meaning he cannot say what he is thinking and feeling. This “paralysis” in the face of fear and uncertainty mirrors the condition of stuttering. As Shell states, Hamlet’s predicament is “at least as much about the kinesis (movement) following stasis (non movement) as about the stasis.”

The Enabling Disability

Shell builds a case for speech disfluency being a partial explanation for Hamlet’s complex behavior. Not completely involuntary, it is one of his ways of stalling for time while he tries to sort things out and stay alive. Using stuttering (or any disability) to one’s benefit is described as “enabling disabilities.” This also comes into play in an analysis of the next subject, Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn Monroe and Identity

Marilyn Monroe exhibited many secondary characteristics typical of a covert stutterer, including a sing-song breathy voice that some have pointed out resemble a therapeutic treatment for stuttering at the time, although she never claimed to have taken therapy. By her own account, she stuttered as a child, and it returned when she was older, although in a covert fashion. For Shell it is her singing that is the key to understanding her relationship with language and identity.

Music and Speech

Shell describes Monroe’s musical performances as “revealing motivating links between music and speech,” particularly her renditions of the classic songs Irving Berlin’s “Heat Wave” and Cole Porter’s “My Heart Belongs to Daddy”. These songs, from two of her most famous movies, feature her unique phrasing that includes breaks, filler words (well, uh…) and repetitions, while backup singers fill in words during pauses. This technique “mimick[s] the stutterer/listener relationship.” Also, by blending singing and talking, she maintains the narrative purpose of the songs, and their context within a larger story.

Why can so many stutterers sing fluently? The main explanation is that singing discards semantic meaning from words and speech, bypassing the physical, mental and environmental cues that trigger stuttering. According to Shell, “Monroe [compensates] for her own intermittent paralysis of tongue by incorporating a [voluntary] stutter.” Stuttering is also alleviated by role playing, a phenomenon that points to the relationship between speech and personal identity.

Let’s Make Love

In the 1960 movie Let’s Make Love, a French millionaire living in New York (Jean Clement played by Yves Montand) is intrigued when he hears of a local play in which he is satirically depicted. Visiting the set, he falls in love at first sight with the play’s star, Amanda (Monroe). He pretends to be an unknown actor, auditions for the role of himself, and gets the part.

In order to convincingly portray a comedy actor playing himself, Clement needs to learn to walk and talk “dumb.” This means, of course, walking like a spastic and talking with a stutter, “duh-duh-duh.” Before the days of political correctness movies and popular songs presented stuttering as the object of mockery, from gentle ribbing to outright ridicule. In women it was seen as “cute.” Underneath the playful condescension lurks the profound discomfort “abled” society has with stuttering, that, like other disabilities, undermines social expectations and is an affront to "normalcy."

It’s not hard to see how Let’s Make Love reveals common attitudes towards identity and social class. For Shell, this is significant, given the magnitude of Monroe’s own deep-seated identity crisis, her early days of poverty and illegitimacy and her mother’s mental illness. The tension in the plot of Let's Make Love comes from the audience not knowing when, or how, Amanda will discover that the actor is the real Clement. He, too, is on a quest to “reveal” Amanda, even spying on her to find out where she lives. Upon the confession that he is really Clement, she doesn’t believe him. The lie had become stronger than the truth.

Stuttering or Pushing Back?

It is curious that few, if any, of Monroe’s co-stars, directors, friends, ex-husbands, teachers, or foster parents, describe her as having a stutter -- rather they claim she was “shy,” “overly sensitive,” “had a bad memory” or “experienced mental blocks.” This is not to suggest Shell is wrong when he asserts that “Marilyn Monroe stuttered.” After all, covert stuttering can go unrecognized, and be disguised as other things. (Notably, there are instances of Monroe talking in her normal voice with no disfluencies, such as the video below of her presenting an award at the 1951 Oscars.) It is telling that some saw her behaviour as a way of acting out. While stuttering is typically perceived as a loss of control, the opposite can also be true, as any stuttering child knows, confronted with the vexation that their “different” speech arouses in parents and other authority figures. Like any disruptive force, it can also wield power. Is it any wonder that Monroe’s difficulty with line delivery became worse as time went on, as if with the full realization that she would never be in control of her career or public image? Like Clement in Let's Make Love, she is locked in the caricature she created, an infantilized hyper-sexual woman, a “babe” who longs for a “daddy.”

That’s What You Think

People who experience stuttering as children can carry its residual effects into adulthood, even when the problem goes away. Their first experiences with speech were so problematic, the simplest of social encounters fraught with uncertainty on so many multiple levels that the anxiety of it persists. After all, the most basic self-identifying information, one's spoken name, is the first thing stuttering devours. When Marilyn Monroe says I stutter does she really mean I can’t tell you who I am?

The fact that there is not a lot of documented evidence or third party corroboration of her stuttering begs the question that Shell does not ask: are you a stutterer if no one hears you stutter? But it is not his goal to question the authenticity of someone’s stuttering, nor it is not easy to see how that would be measured. He is guided both by a starstruck fandom and his background in linguistics and comparative literature, weaving in references to dadaist theory that questions the ability of language to contain meaning, and the use of the “lazy” schwa vowel so commonly found in stutterers’ speech. Marc Shell presents an uncommon perspective on one of the most famous women of the twentieth century who continues to fascinate, and who, despite being filmed, photographed, and chronicled a multitude of times, will never be fully revealed.

Read part 3 here.