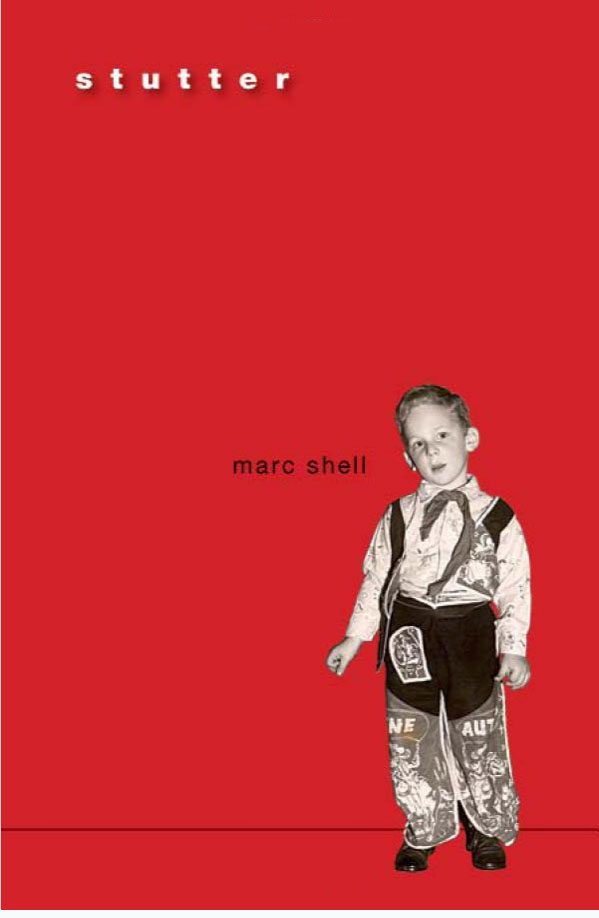

The familiar saying “you can’t judge a book by it’s cover” has never been more true than when applied to Marc Shell’s Stutter. A photo of the author as a small child wearing a cowboy outfit graces the book jacket, his innocent face both quizzical and apprehensive.

Shell, a Harvard professor of comparative literature, describes the book in the introduction as “to some small extent a sort of memoir.” His reluctance to characterize the book as personal is understandable -- most of Stutter is a dense, academic yet fascinating treatise on history, linguistics, popular culture, religion, semantic deconstruction and social theory as it pertains to four specific culturally significant figures who are associated with disfluent speech. Shell sets the bar high as to what a close study of stuttering, in this context, shall yield; he seeks to explore the interplay between mind and body, the will and the spirit, and, “open up for reflection the gap between the involuntary and the voluntary.” Furthermore, an analysis of stuttering “provide[s] access to the neurological and evolutionary roots of human language, the history and purpose of song, and the roots of legislation.”.

Influences

Born in Montreal, Marc Shell’s early life was impacted not only by stuttering but by contracting a crippling case of polio, rendering him impeded by physical limitations of two different natures. Also informing his perspective is his Jewish upbringing and education, exposure to a bilingual culture, bouts of chronic depression in his adult years, and ongoing personal fascinations with ventriloquism, Hollywood, slapstick comedy and the interplay between high and low art.

Stutter explores the nature and implications of defective speech as it applies to a diverse quartet of characters both historic and fictional: Moses, Marilyn Monroe, Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, and Warner Brother’s Porky Pig. According to Shell, their stuttering is not a postscript; rather it is crucial to their identities and “integral to what they accomplished.”

The review of this book will be published in three parts. Part one will review the chapter on Moses called Moses’ Tongue.

The reluctant Moses

That Moses was a reticent speaker is well documented in biblical texts. He describes himself as “impeded of speech". Given the profoundly oral culture of the time, to struggle with the spoken word would have been a significant burden. Unlike Egyptian and Midianite, the Hebrew language did not even exist in written form. Moses was adopted as an infant by Egyptians, and at age forty joined the Midianite people into whose culture he married and had a family. He was no doubt tri-lingual, and given his cosmopolitan upbringing, better educated and literate than, say, his brother Aaron. But Moses was never truly immersed in Hebrew society, and no doubt found himself alienated from it, the way those who grow up straddling more than one culture can end up belonging to none. It is not surprising that Shell attributes Moses’ discomfort with speaking as having as much to do with his fragmented ethnic identity as with a physical impediment..

Are you one of us?

To emphasize this point, Shell devotes a chapter to discussion of the shibboleth, an ancient test of word pronounciation that various tribal groups used to determine if a stranger was “of their people.” It was not a casual inquiry: to fail a shibboleth test could mean anything from social exclusion to exile to execution on the battlefield -- grave consequences for disfluency. No wonder Moses was afraid. As Shell points out, “for the stutterer, every word is a test word.” No doubt Moses would not “pass the test” among the very people whom he led, just as the stutterer -- regardless of the degree of status and success he achieves in life -- is never quite rid of the sense of being an outsider among his own people. Yet it was precisely this “outsider-ness” that made Moses ideal for the dual role of liberator and law-giver, and to demonstrate the non-representational nature of a God who was to be perceived in the realms of thought and feeling rather than words or idols.

Stuttering and legislation

Is there a connection between speech dysfunction and political language? Shell suggests yes. He lists numerous legislators throughout history who struggled with disfluency. The emperor Claudius introduced new language laws, including the addition of three new letters to the Roman alphabet. In July of 1789, an obscure notary named Camille Desmoulins addressed a crowd in the streets of Paris, despite the fact that he stuttered. He was the first to call the public to arms, helping to launch the French Revolution. He had to give up on a career in law and turned to publishing, and supported the people’s revolt with political literature and pamphlets.

The idea that stuttering would cause one to be drawn to politics, whether to make laws or revolt against them, is a fascinating thesus if not substantiated here. But Shell is convincing in his argument that Moses’ speech deficit is an integral part of his life story and character as well as of the broader historical context, and that this has implications for the historical and religious significance of disfluent speech.

You can purchase Stutter here.

See the next installment: Marilyn Monroe and Hamlet