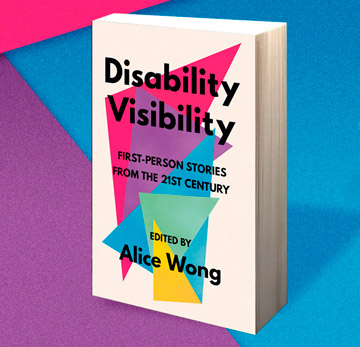

Disability Visibility: First Person stories from the Twenty-First Century, is a collection of essays by and about disabled people. Editor Alice Wong is an award-winning writer and activist for disability rights. She created the Disability Visibility Project to record oral histories of disabled people. As well as running a web site and a podcast, she recently published this anthology.

While there is not a story about stuttering in Disability Visibility, that doesn’t mean there isn’t something for people who stutter to take away. For instance, the essay “When You Are Waiting to be Healed” is by a woman with deteriorating vision caused by a congenital eye defect, something numerous operations failed to correct. With more operations scheduled, and a religious family that expected divine intervention to help heal her, she is shocked when a specialist recommends that she apply for disability benefits.

She writes, "Saying that I had a disability felt like I was adding ink to a penciled truth… I had grown up surrounded by people who undermined the severity of my disability, and so for me to claim the label, when I didn’t feel ‘disabled enough’, felt disingenuous…. [it] felt like landing myself with an unecessary burden."

Ultimately, she finds that accepting the label of “disability” is a relief, after decades of holding out for surgical, or divine, success. Most people who stutter have, from childhood, had fluency dangled in front of them like a carrot to a mule - speech therapists telling us to ‘work harder,’ simplistic advice from listeners to "breathe” and “slow down,” as if they are saying that, while there is no cure, stuttering is something that can, and should, be fixed to the extent that one can pass for normal. Do people who stutter resist the label of ‘disability’ because it means surrendering to its permanence? Do people who stutter resist the label of ‘disability’ because it means surrendering to its permanence?Harriet McBryde Johnson was a well-known activist, writer and attorney specializing in advocating for the rights of the disabled. A degenerative neuromuscular disease twisted her spine and confined her to a wheelchair. As a youth, she wore a back brace, but chose not to have a metallic rod fused to her spine that would maintain the upright posture permanently. The procedure does not provide comfort or mobility for the disabled person — quite the opposite. It is for appearances. Harriet's essay is reprinted from the New York Times. She writes, "At fifteen, I threw away the back brace and let my spine reshape itself into a deep, twisty S-curve… Since my backbone found its own natural shape, I’ve been entirely comfortable in my skin."There is an expectation that disabled people should "fix" themselves to the extent that they can, even if it's just to make “normal” members of society comfortable. People who stutter, who often prize fluency above all, struggle to achieve fluency and then find themselves in a Sisyphean battle to maintain it. In striving to be normal, do they sacrifice their own well being?

Intersectionality

Disability rights has evolved into a broader conceptWhat actually constitutes "disability"? Thirty years ago, the concept of neurodivergence was an obscure topic, but Disability Visability features voices of those who place on the autism spectrum. Disability rights in general has evolved into a broader concept – that of intersectionality. Disabled people who also happen to be women, people of color, gay, trans or of any other marginalized group, should not have to fight against specific forms of discrimination individually. They are more effective advocating as a group rather than addressing isolated components of who they are, a better way to solve problems around rights for marginalized individuals.

Yet the struggle for the "intersectionality" approach to disability rights has met resistance from unexpected places. The essay featured by the Harriet Tubman Collective relates their disappointment when they failed to get the Movement for Black Lives to include disabled rights in their manifesto, as they had for the LGBTQ community. "If a staunch political stance is going to be taken about the Black experience," they write, "it is a grave injustice and offense to dismiss the plight of Black Disabled and Black Deaf communities."

A New Generation and Disability Justice

Marginalized people can help each other in real, tangible waysOne of the best writers in this anthology is Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, with her essay. "Still Dreaming Wild Disability Jutice Dreams." She does indeed dream wild. In the terms of Disability Justice, the movement is anti-capitalist, pro-sustainability and commited to cross-disability solidarity. It's not just about intersectionality, but also interdependence, where marginalized people help each other in real, tangible ways. For instance, there is a group that arranges for air purifiers and generators for those with respiratory illness or who rely on medications requiring refrigeration during power outages.

Piepzna-Samarasinha is also critical of the "old guard" of disability activists, who in her mind, stuck too much to working within the system, tweaking policy. Their emphasis on “independent living” ignored the true collective power disabled people have to unite and help each other, something more than "support group sessions" that amount to little more than unproductive griping. For all their successes, disabled people are still begging for scraps and apologizing for their existence. "The existing structures of paid care attendants are unnderpaid, abusive, and difficult for many of us to access," she writes, "Where are our dreams of a collective mutual-aid network, of a society where free, just, non-gatekept crip-led care is a human right for all?" It is a dream worth not only dreaming, but achieving.

Disability Visibility is a fascinating anthology for those interested in disability rights. A reader might think, however, that more disabilities could have been represented -- stuttering, Tourette’s Syndrome, epilepsy, schizophrenia and multiple sclerosis to name a few. Some of the stories are as short as three pages and there is a bit of repetitiveness. One of the longest essays — about the inefficiency of the ParaTransit system in New York and its sometimes disgustingly rude drivers, while well written, does not really add much to a reader’s insight into the disabled experience. An index would make the book easier to use as a reference tool. But all in all, Disability Visibility is a fine compilation with passionate writing and constructive ideas that look to future possibilities and dreams for disability rights and justice.

Lisa Wilder is on the Board of Directors of the CSA and lives in Toronto.