One of our members, Peter Holleley, was in a serious human rights dispute with the Landlord Tenants Board (LTB) which he then escalated to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO). CSA is supporting him and reaching out to see if there are other PWS in Ontario or the rest of the country who have had problems with the LTB, or any negative experience of being in a legal system where stuttering is not accommodated for. He is also looking for legal advice from a lawyer or paralegal. If you can help or support the mission of legal rights for PWS, and folk with other invisible “iceberg” disabilities, please contact the CSA with attention to Lisa Wilder.

An Unbearable Situation

Peter is a senior citizen living in Toronto on a fixed pension. He has a significant lifelong stutter, functional dyslexia and various age-related ailments and other impairments. Also due to a disability, he finds it difficult to use computer screens. In the past couple years he has experienced major health issues, including a stroke, a fall, and hospitalization.

Three years ago in 2021, an ongoing cockroach problem in his apartment building became unbearable. Peter decided to withhold $600 of his rent as compensation for having to live with the health hazard the infestation had created. He had legal advice that he could do so as the landlord had not dealt with the problem. When the landlord launched a Landlord Tenants Board (LTB) action against him, he was required to present his case to the Board.

Denied an In-person Hearing

The LTB used to hear all cases in person, but the pandemic forced hearings onto video or telephone platform. This makes it harder to present evidence, especially for inexperienced and sensitive litigants who feel overwhelmed by remote communications, speak English as a second language, stutter, or a host of other disabilities. For this reason, and in line with Human Rights legislation, the LTB is required to offer in-person hearings when a litigant applies for one.

The Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 (AODA) classifies Peter as “disabled” and entitled to accommodations. But when he applied for an in-person meeting to present his case, it was summarily refused. Due to his trouble with screens, he had no choice but to use the telephone option.

A Traumatizing Phone Call

The session Peter ended up joining was an over-crowded multi-person conference call, in which claimants wait in line to make their case. As he describes it, “As instructed, I began the log in procedure at 12:30 pm for a 1:00 pm start. There was a multitude of others on the same call all seeking attention, “Me First!” It was bedlam, very intimidating, I had to concentrate hard to listen for my case number or name to be called. I was literally panting for breath. It was an excruciatingly traumatic experience that debilitated and crushed me.”

In fact, Peter characterizes the debacle as “Cruel and unusual treatment” (a Charter section 12 violation). He continues: “…approaching 5:00 pm when I heard my name, I was simply too exhausted to speak coherently, let alone present and discuss my evidence; I asked for and was granted an adjournment.”

In the past, Peter has self-represented successfully in-person in family courts. To be effective and fair, his LTB case needs to be face-to-face.

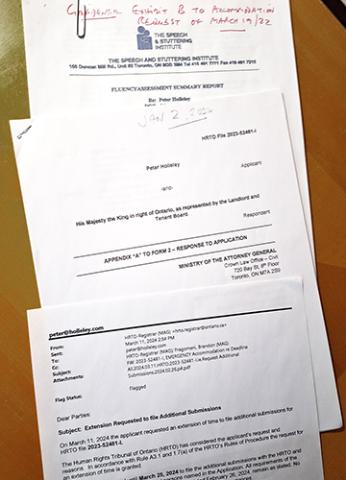

In March 2022, he received the summons to another virtual hearing later that month. He again asked for an in-person hearing and submitted personal medical information, including a three page Fluency Assessment Summary Report from the Speech & Stuttering Institute. Yet again his request was summarily declined and he was forced to join another multi-person call.

Rights Further Denied

“Again I had to sit on the edge of my seat for hours struggling with the mayhem and dreading the moment when I'd hear my name,” says Peter. “Eventually soon after 4:00 pm I did. Too stressed and exhausted to think and speak in full sentences, I opted for mediation.”

As he describes it, “The mediator introduced herself and then bomb shelled me by saying that, if I agreed to a payment agreement and then failed to pay, I could be (I heard, “I would be”) summarily evicted without recourse. Dumbfounded and panicky, I managed to insist that IF I paid the outstanding $600 plus the landlord’s $183 fee, THEN my roach-related evidence absolutely WOULD be heard on another day. She PROMISED that this would appear in her written report. Again, I was panting to breath, spitting out my words one by one; ghastly! As she promised it did appear in writing but was then forgotten until I was able to get the Office of the Ombudsman to intervene months later. This whole extended LTB escapade was clearly more “Cruel and unusual treatment” (a continuing Section 12 violation).”

Peter is convinced that the LTB had conspicuously violated his Constitutional Freedoms, He says, “Pursuing my case since has been, continues to be, a living nightmare with not a glimmer of light where there should be light. Being dyslexic, even the usually simple task of organizing files and paperwork is a challenge.”

An Ongoing Issue

Peter is currently still dealing back and forth with the HRTO and the LTB’s legal counsel, and now seeks an in-person hearing with the HRTO. The question of legal standing and justice for people who stutter in situations like this – where they are not granted accommodations for their disability – needs to be addressed by all of our court systems. This is an important mission so please contact us with any support or advice that you can offer. Thank you.