I have very little control over my stutter. I wouldn’t even call it control; it’s more like I have to bargain with it. “Hey Nina’s Stutter, if I put on my ‘business voice’ and totally not sound like myself, will you let me get through this one phone call with a stranger?” “If I allow this word or that word, will you at least stay out of my next sentence?” I get exhausted just thinking about it. If I planned my day around Nina’s Stutter, there wouldn’t be time for anything else. Life is short, and I’m not going to waste it trying to control what I can’t control.

Life's Constant

Stuttering is one of the few constants in my life. My hair has changed, my clothes have changed, my address has changed—but Nina’s Stutter is here to stay. It has never changed, and it probably never will. But the way I think and feel about it has changed.

I used to hate Nina’s Stutter. I was ashamed of it. I devoted the best parts of my youth to fighting it, instead of doing things that made me feel happy or productive. The more I missed out on life, the more I blamed Nina’s Stutter, doubling down my efforts to kill it. If only I were fluent, everything else would fall into place! I could speak freely. I could have boys ask me to prom. I could even follow my dreams and be a stand-up comic. All I had to do was stop stuttering!

When I write it down, it seems so ridiculous. How can some pauses and a few extra syllables take control of a person’s life?

The Iceberg Metaphor

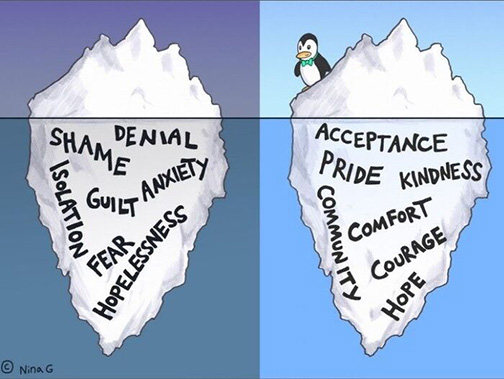

That question became a point of focus for Joseph Sheehan, a clinical researcher and psychologist. Throughout his career, he observed that stuttering was typically more disruptive to a person’s emotional wellbeing than it was to their actual speech. In Stuttering: Research and Therapy (1970), Sheehan writes that “stuttering is like an iceberg, with only a small part above the waterline and a much bigger part below.”

According to Sheehan, what most people think of as “stuttering” is only the tip of iceberg—the outwardly observable symptoms on the surface. But the emotional baggage that it carries—the invisible pain underneath—that’s the bulk of the ice.

Sheehan organized these murky, underwater emotions into seven categories: fear, denial, shame, anxiety, isolation, guilt, and hopelessness. According to Sheehan, as the stutterer resolves these issues, the negative emotions begin to “evaporate.” This in turn causes the “waterline” to lower, until, finally, all that remains is the physical stutter.

An Inspiring Holistic View of Stuttering

Sheehan’s book became highly influential in its field. The iceberg theory advanced a more holistic view of stuttering, inspiring professionals to consider more than just fluency techniques. It also helped me think about my own experience. I have all those emotions below the water. I have felt guilty, for making people wait through a stalled sentence. I have felt isolated, especially before discovering the stuttering community. But most of all, I have felt shame, simply for speaking the way that I speak.

Although it provides a useful framework, I don’t think Sheehan’s Iceberg presents the full picture. Sure, it explains the negative things we feel, but what about the other emotions? Just like everyone else, the life of a stutterer is filled with ups and downs, victories and defeats, good times and bad times. Even if your overall situation doesn’t change, things might look better or worse on a given day depending what side of the bed you wake up on. It’s all a matter of perspective.

Changing Perspective

If you’ve ever laid on the grass and looked up at the clouds, you know how easily perspective can change. One minute this cloud looks like a dragon; the next minute it looks like a bunny rabbit. Unless El Niño is brewing up an apocalyptic tornado, that cloud probably hasn’t changed much in the last sixty seconds. Instead, you let your eyes wander, reoriented your perspective, and unknowingly formed a different mental picture of the same thing.

If it can be done with literal clouds, then it can be done with metaphorical icebergs. Stuttering doesn’t have to be a bad experience if we change our perspective. Before I found the stuttering community, my perspective was all negative. I was isolated, ashamed, and everything else Sheehan packs into that sad popsicle. But when I found the Stuttering community during the summer in high school, something changed. I was no longer isolated–I had found a community. I had reduced my shame and was even maybe proud?

Sheehan writes about negative emotions evaporating until only a stutter remains. I disagree. When bad feelings subside, other feelings have to take their place. We don’t refer to happiness as “not sadness,” or confidence as “not embarrassment.” The negative emotions in Sheehan’s Iceberg all have positive equivalents. I propose that we can do more than simply make the bad feelings go away; we have the power to transform fear, shame, anxiety, isolation, denial, guilt, and hopelessness into feelings of courage, pride, comfort, community, acceptance, kindness, and hope.

Accepting, and Loving, Ourselves

So how do we do that? Although the negative emotions in Sheehan’s Iceberg are common to the stuttering experience, they are common because we live in a society that treats people with disabilities as substandard. But we don’t have to buy into it. All the weird looks we get in public, all the un-empowering images we see in the media, all the lowered expectations that people project onto us — they can all be thrown out and replaced with something better. Instead of struggling to conform to the ideals of a culture that makes us feel deficient, we can cultivate our own perspective and learn to love ourselves as we are. Every person who stutters has the responsibility to create their own iceberg—one that reflects their best possible self.

How we are perceived is largely influenced by how we perceive ourselves. When I began to accept my stutter, so did the people around me. Friends and family stopped offering advice on how to improve my fluency. Obviously there is a limit to how much self-perception can determine the views of others: I can’t force someone to stop being a jerk. But I can determine my own worth.

Promoting stuttering acceptance is important for people who do and don’t stutter. Everyone who interacts with us, thinks about us, studies us, works with us, produces movies and TV shows about us, reports on us—they all have stuttering icebergs too!

Changing Attitudes

The strange and uninformed ways they treat us stem from murky emotions below the tip of the iceberg. If we are ever going to overcome discrimination, we have to address the emotional baggage we all have around stuttering and disability in general. It’s not going to be easy. It’s hard enough to understand my own feelings toward stuttering, much less model them for others! All I can do is put myself in front of the public and try my best—in bars and comedy clubs, on college campuses, in online videos and social media.

Changing attitudes and perceptions is important for ourselves as well as for our society at large. I appreciate those allies who see it as part of their mission to challenge these and walk along side of us to do this work.

Nina G is a Stand Up Comedian, Author and Professional Speaker. Check out her web site at www.NinaGcomedian.com