In 1936, a statuesque 20-year-old named Mary Dowell was hired as a dancing girl for an extravagant Texas Centennial celebration in her home town of Fort Worth. Until then she had been, in her own words, “looked upon as a sort of freak” due to her height and pronounced stutter. “When I walked down the street people would look at me and grin, like I was the town idiot. I was the unhappiest girl in Texas.”

The Showgirl to End all Showgirls

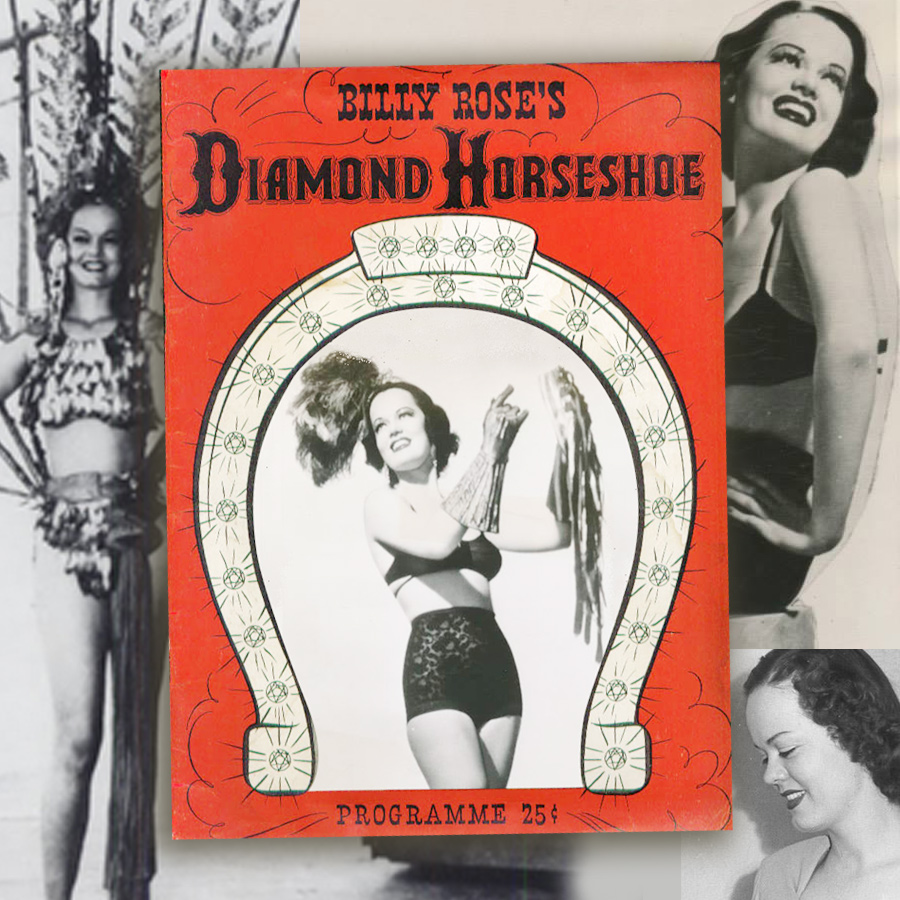

Mary would go on to become one of the most famous stars of her day. Before the ascent of Hollywood and television, live Broadway style shows were the apex of entertainment, and in the late 1930s, Mary was the toast of New York. One of her directors at the famous Diamond Horseshoe nightclub where she performed, who gave all the showgirls nicknames because it was easier than remembering their real names, christened her “Stuttering Sam.” Mary was not offended, remarking “it was the most natural thing in the world to call me.” 6’3” in heels, with a captivating stage presence, reviewers called Mary “one of the most astonishing showgirls to ever hit New York,” “the showgirl to end all showgirls” and a “full-fledged Broadway institution.”A Texas Rose who Charmed New York

Diamond Horseshoe

Club owner and show producer Billy Rose, who discovered Mary in Fort Worth and brought her to New York, claimed she was the ideal Broadway showgirl, because “the fact that she stutters, does not interfere in the least with the conventional show girl pattern, for these young ladies, like children, should be seen but not heard.” One director suggested that she could stop stuttering if she just “stopped talking,” and got so annoyed by her speech during a party at his house that he threw a book at her head.

None of this phased Mary. Texas has never been known for its shrinking violets, and Mary was an unpretentious, sparkling personality with a charming naivete, who talked to everybody without an ounce of bashfulness about her stuttering. Cynical New Yorkers were delighted with her forthright wit and guileless nature and her tales of life growing up on a ranch where she had fed chickens, milked cows and churned butter. Billy Rose was reportedly jealous when a columnist noted that “Mary could look out over the audience on a night at the Diamond Horseshoe and know more people than Billy does.” Indeed, even people from Fort Worth who used to laugh at her came to see her in New York, begging for her to join them at their tables after the show.

Her Own Person

The clone-like showgirls of Broadway did not typically gain individual popularity, and this made Mary unique. She was conflicted about her fame, however, and although she loved performing she considered the Broadway showbizness scene frivolous. She joked that she got “fired every day” for things such as “throwing her costumes on the floor, shaking her hips differently from the other chorines, coming in late and acting stubborn.” But actually, she had such a good rapport with nightclub management that her fellow dancers elected her to be their spokesperson when issues arose.

There was nothing covert about her stuttering, often to the astonishment of those who met her. One reporter, interviewing her for an article in a newspaper, marvelled at it, claiming she blocked on every second word. “If I undertook to write this interview in the precise manner in which it came out, it would cover this entire page and run over into the sports section, for it is a report of a conversation with Stuttering Sam,” he wrote, and noted that it took her fully three minutes to say the two words ‘60 acres.’

A Thrilling and Challenging Life in New York

In one interview she remarked, “I like New York. I’m still 6 feet tall and I still stutter, but nobody holds it against me, and I have a million friends here, and not one cow among them. I hope I never see a cow again, or a churn.” but her love affair with the big city soured. In fact, in 1938 Mary was involved in what could be called a scandal, when she was assaulted in a taxi cab by a man she identified only as a “U.S. Senator.” He punched and kicked her when she tried to leave the cab, giving her two black eyes and sore ribs. “I’m going back to Texas and wrestle steers,” she proclaimed, “At least a girl doesn’t have to fight with them in taxis!”

This incident was covered in papers nation-wide, but the reaction was not what we, in more enlightened times, would expect. Her fellow dancers made fun of her black eyes, and columnists turned on her when she complained about the hardknock life of New York. She was accused of being ungrateful, a diva, and looking for publicity, with one columnist declaring “we should send those Texas girls back to where they came from!” The most outrageous piece denounced her for the “scorching indictment” of her adopted city, and pointed out that punches were often thrown during rowdy nights at the Horseshoe. Photos of other showgirls with black eyes and one with a visibly broken nose were featured, as if to say it wasn’t that big of a deal. It is shocking to see violence and assault so normalized — times were certainly different.

A Career Change, and Moving to Los Angeles

in Los Angeles

Mary moved back to Texas for a while, but, missing the excitement of her big city life, returned after a couple months. She was still the star of the show, bringing down the house with her dancing, stage presence and impersonations she did of stars like Greta Garbo. By 1941 she was aging out of the showgirl scene, and took her typewriter to Hollywood to follow her dream of becoming a script writer. Writing was natural to her, a skill she gained as a kid when school teachers made her write out answers to questions on the blackboard instead of saying them. She wrote episodes for a TV crime drama and did uncredited work as a movie “script doctor.”

The famous director Howard Hawks was interviewed in 1976 for a compilation of film essays, Selected Film Essays and Interviews. It was common for different writers to work uncredited on a single script, and he revealed that Stuttering Sam wrote dialogue for his movie, To Have or Have Not.The interview contains this (reproduced here as it appears)

There was a girl that was pretty good, a former chorus girl…. She was exactly my size, and she st-st-st-stut-stut-stut-stuttered. Her name was Stuttering Sam. She could write letters but she cou-cou-couldn’t talk. So I hired her to come out and do some dialogue and she did some beautiful dialogue — utterly untrained as far as pictures are concerned — and I’d have her around still but she married a guy with about $20 million, and is very happy.”

— Howard Hawks, intervied by Bruce Kawin

A Return to New York

in Los Angeles

But Mary’s writing career, although marginally successful, did not gain steam. Never short on suitors, she did indeed marry a millionaire businessman thirty years her senior. When he died, she wed again, to another man of wealth, ad executive Guiles Copeland, and they moved back to New York. She returned to show business for a while to work as a publicist for her old boss Billy Rose, a gig that lasted a couple years.

Mary often spoke about writing her memoirs, but sadly it was not to be. She died in 1963 at age 48 of a rare blood disease. There were many columnists around who fondly recalled her days as a showgirl, and obituaries ran in papers across the country with sentiments such as “a little of the sparkle had gone out of Broadway”, “gee, that dame has class” and “she had the nicest, brightest, kindest face in show business.” A few who knew her well spoke of her more reserved and thoughtful side, with one writing “In the midst of Broadway’s dregs...Sam just went her serene way.” He also shared a line from one of her favourite poems that she often quoted, The Old Astronomer to his Pupil, by Sarah Williams, “I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night.” The story of Mary Dowell is a tale of a woman with an indomitable spirit, from a time long past, who was her own person and enjoyed a festive, full life that ended too soon.

Mary was laid to rest in Fort Worth, Texas.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

From Newspaper Archives

The Indianapolis Star, 26 Dec 1941, Columnist Alan Smith

Daily News, (New York) 6 Feb 1939, 18 Feb 1940, Columnist Julia McCarthy, various articles

Star Tribune, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 20 May 1938

Fort Worth Telegram, various articles, 1938-42

El Paso Herald Post, 28 Aug 1939

San Bernardino County Sun (San Berdino) 19 Feb 1940

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 14 Feb 1954

The Kane Republican (Kane, Pennsylvania) 24 April 1963, Columnist Mel Heimer (obituary)

News Press (Fort Myers, Florida) 13 April 1963, Columnist Whitney Bolton (obituary)