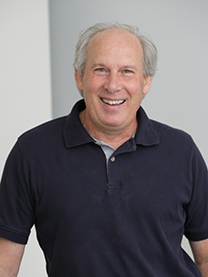

Dr. Dennis Drayna is a human geneticist well known to the stuttering community for his renowned work researching the genetic basis of speech disorders. His team has made groundbreaking discoveries in the field and he has frequently appeared at conferences to share his findings. In April he was interviewed by Ben Chambers on the podcast Speaking of Science. Here is a summary of the interview.

Dr. Drayna and interviewer Ben Chambers start their discussion talking generally about stuttering. It is a puzzling disorder, and researchers are still trying to figure out the cause. Drayna was surprised, when he first started studying it, just how detrimental it could be in people's lives. It is different from other neurological disorders in many respects. Although it is not a psychological condition, there is an undeniable psychological component to it, as it is exacerbated by emotions, social anxiety and people's expectations. Many people who stutter make the observation that "no one stutters when they talk to their dog."

Genetic Basis for Stuttering

Drayna's team has identified four genes associated with stuttering, and mutations in these genes are found in 20% of people who stutter. As for the remaining 80%, they haven't yet found the genes responsible. The research shows that some fundamental mechanisms within cells that involves the moving and recycling of things are damaged, causing disruption in the speech mechanism. How these mutations cause stuttering is not known. Drayna comments that an extraordinary thing about stuttering is its specificity: in the majority of cases no other human function is effected. The fact that a deficit in particular neural cells interferes with speech means there could be an undiscovered part of the brain uniquely dedicated to the speech function.

The Current State of Treatment

Drayna treads carefully when he talks about the effectiveness of speech therapy. In the realm of communication disorders, stuttering is known to be particularly hard to treat, and does not have high clinical outcomes. This is not the fault of speech therapists, but indicates that gene therapy or pharmaceutical treatments might improve the success rate. The problem with developing pharmaceuticals is the enormous cost of research and development. Drayna says how pleased he is to be working at the National Institutes for Health (NIH) where experts from different medical fields discuss and collaborate on their work, something that has helped immensely.

The Cameroon Connection

A major breakthrough in Drayna's research came with the discovery of a large family in Cameroon where stuttering was common. A man with 21 siblings (his father had three wives as polygamy is practiced there) contacted the Stuttering Homepage to ask about the hereditary factor of the condition. He, all his brothers and sisters and many other members of his enormous extended family stuttered. Studying this family enabled Drayna to identify the fourth gene connected to stuttering.

"Stuttering" Mice

The interviewer and Drayna discuss how there is still a huge gap in research. Scientists are limited by the fact that invasive experiments cannot be done on live humans and there are no animals who talk to use as test subjects. However, animals do vocalize. Mice have complex vocalization, although it is not perceptible to the human ear. Using microphones, Drayna's team studied the way mice "squeak/talk" before and after they engineered the stuttering gene mutations into their genes. The effected mice displayed gaps in their squeaking. This research is still ongoing, and could lead to a breakthrough in treatment.

the Origins of Language

Why is anxiety so connected with speech, and not just in people who stutter? Drayna points out that while language is unique to humans, it is based on genes that are not. Animals typically vocalize as an expression of fear, danger or excitement, the way humans scream when on a rollercoaster. Modern psychologists have termed it the "primal scream." It is interesting that human language can be traced back to this connection with highly stressed states. On some level we have not completely disassociated speech from fear, something all the more obvious in people who stutter.

This interview is quite interesting, and consists of two one-hour segments. See part one here. You can also learn more about Dr. Drayna's research here.